The compilation of anthologies of excerpts, that is to say, the selection and transcription of passages deemed important while reading a text, is a common scholarly practice in Byzantium: excerpts were essential to the way Byzantine intellectuals managed information. Very often, collections of excerpts were compiled close to the moment of reading, either simultaneously or shortly after; therefore, they faithfully record the reading experience of their compilers and provide useful insight in the relationship between readers and their books.

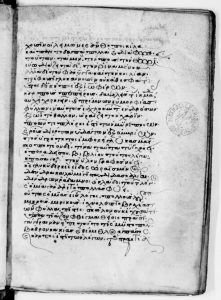

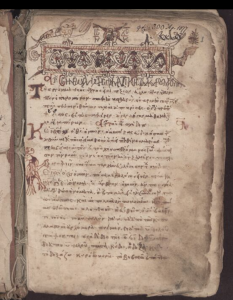

One of the largest collections of excerpts from the early Palaeologan period, MS Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale “Vittorio Emanuele III”, II C 32 sheds light on Byzantine intellectuals’ attitude towards paratexts and their role in the context of scholarly reading practices. Neap. II C 32 is the fair copy of earlier notebooks belonging to a group of anonymous scholars who worked in close connection with the «school» of Maximos Planudes; the codex was transcribed around 1330 by the professional scribe Georgios Galesiotes with the purpose of creating an orderly archive of the scattered papers which had circulated for a few years among the members of the group. It contains excerpt-collections from a wide variety of prose texts, from the Bible to the works of some of the most important Church Fathers (Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, John Chrysostom), alongside ancient Greek (pagan) literature, from history to rhetoric to philosophy.

A close examination of the anthologies of excerpts preserved in Neap. II C 32 shows that the scholars who compiled them were attentive readers of the paratexts of the books they excerpted from: in order to make referencing easier, they annotated not only the names of the authors, but also the titles of the individual works belonging to a corpus (e.g. Demosthenes’ speeches and Plato’s dialogues are all identified in the margins of the folia). Moreover, these same compilers frequently transcribed traditional paratexts (scholia) and regularly added paratexts of their own in their notebooks (usually newly composed scholia, which have been faithfully reproduced in the Neapolitanus).

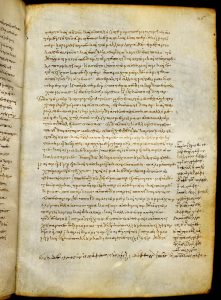

The last section of Neap. II C 32 holds particular significance in showing the role of paratexts in the reading experience of the group of Byzantine scholars responsible for the materials later gathered in the Neapolitanus. This section, corresponding to ff. 366-371 of the MS, transmits a summary of the Iliad that is entirely composed of traditional paratexts which could be found in the many direct witnesses of the poem: the compiler of the summary put together, one after the other, hypotheseis (i.e. “abstracts”) pertaining to each book of the Iliad and prefaced them with a short text summarizing the cause of the war and the first nine years of the conflict, which they were also reading in the same Homeric codex they were excerpting the rest from.

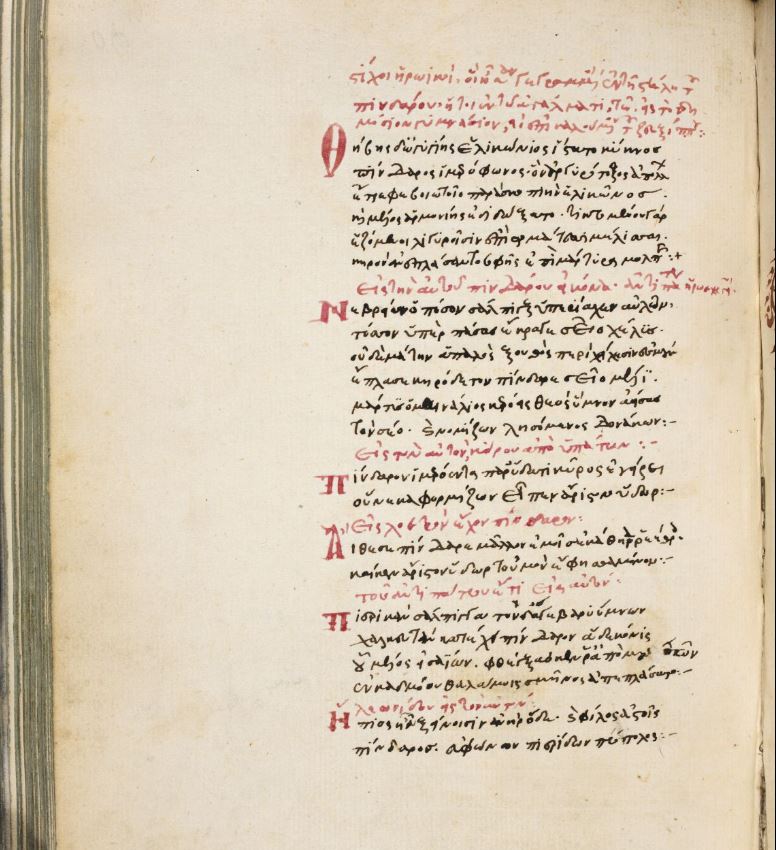

In the Neapolitanus, the hypotheseis are written in black ink and each of them is preceded by a metrical paratext consisting of one hexameter. All the hexameters are copied in red ink, whose employment conveys their role as titles, and they provide key information to orient readers in the understanding of the summary as a whole: the majority starts with the letter/number of the book and continues with a list of events or a single important fact happening in that book. Here is, as an example, the line prefacing the hypothesis to Book Alpha/One:

Ἄλφα λιτὰς Χρύσου, λοιμὸν στρατοῦ, ἔχθος ἀνάκτων.

Alpha contains [NB: the verb ἔχει is sometimes omitted] the prayers of Chryses, the plague in the army, the quarrel of the kings.[1]

(DBBE Occurrence 18434)

These metrical paratexts working as titles circulated widely in the witnesses of the Iliad[2], as the DBBE shows. Embedded as they were into the traditional paratexts of the Iliad, the hexameters played an essential role in the way Byzantine readers approached the text of Homer: editors, scribes, and individual readers modified them or composed some anew in order to highlight the information they deemed important. The presence of these metrical paratexts in the summary of the Iliad transmitted by Neap. II C 32 is witness to the value attributed to this particular paratext. Since the notebooks on which the Neapolitanus is based were compiled in a school environment, these lines, with their prominent position on each page, could not only work as titles for each section of the summary, but also serve as simple memory aids for the content of each book. If memorized or consulted properly, they could be employed as effective reference tools for the text of Homer.

The summary of the Iliad contained in the Neapolitan codex was compiled on the basis of MS Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana A 181 sup. (Martini-Bassi 74)[3], a palimpsest codex whose scriptio superior dates to the early Palaeologan period, between the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th century. By comparing Neap. II C 32 and the Ambrosianus, it is possible to observe how the focus of the compiler of the summary was influenced by the layout of the exemplar they were reading; their gaze was likely oriented by a series of expectations on the place(s) where useful information was located and these expectations played a role in their perception of paratexts.

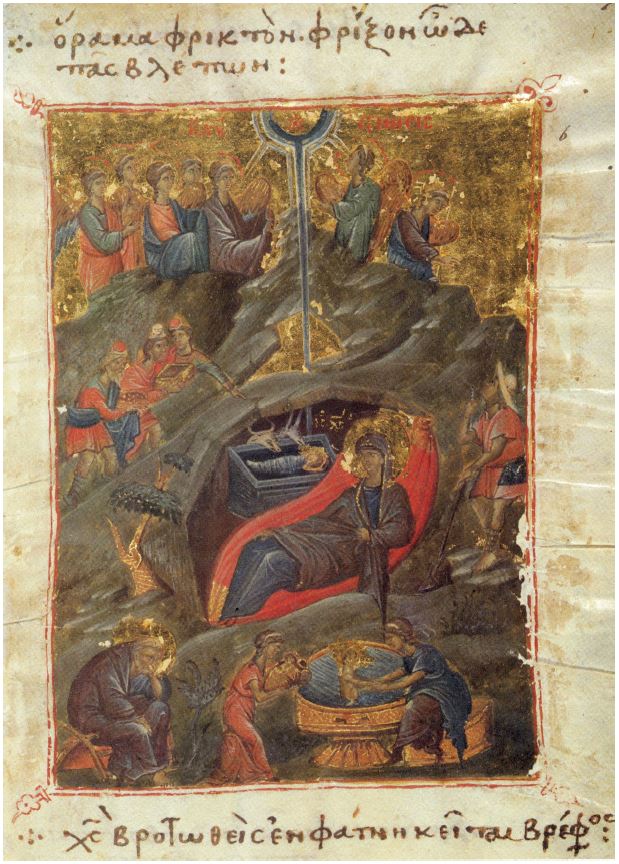

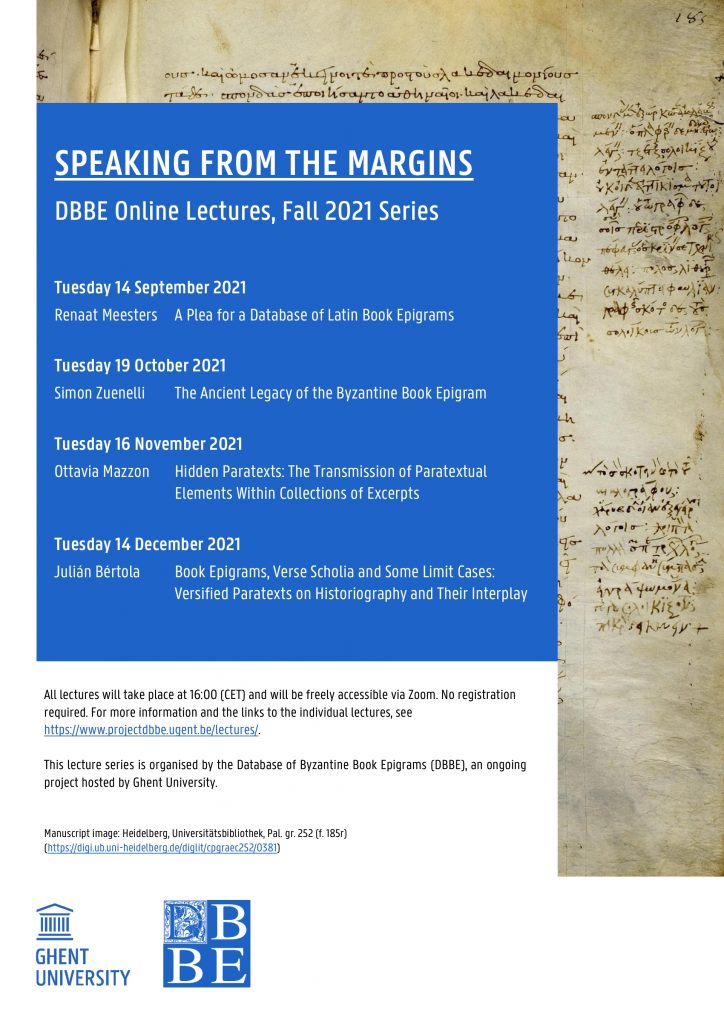

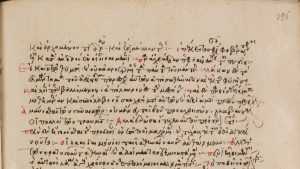

In the Ambrosianus, which transmits the text of the Iliad, the metrical titles are usually found in the blank space after the end of the hypotheseis to each book and the beginning of the actual text, next to the unmetrical titles; sometimes, however, they are written also after one of the hypotheseis, far from the unmetrical title.

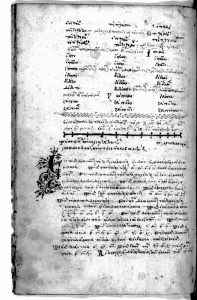

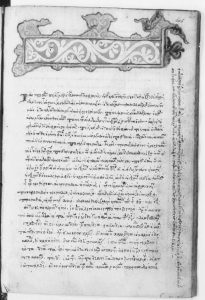

At times, the Ambrosianus transmits multiple metrical titles referring to the same book, each one describing the content in a different way. In Image 2 and Image 3 above, one can read the two lines pertaining to book Kappa/Ten, which were written in two different folia of the manuscript, the first one after the first hypothesis to this book, the second one next to the title:

(f. 48v) Κάππα δ’ ἄρ’, ἀμφοτέρων σκοπιαζέμεν ἤλυθον ἄνδρες.

Kappa: men go out on both sides on an exploratory survey.

(DBBE Occurrence 18434)

(f. 49r) Κάππα, Ῥήσου τὴν κεφαλὴν ἕλε Τυδέος υἱός.

Kappa: the son of Tydeus (i.e. Diomedes) took the head of Rhesus. (this translation is mine)

(DBBE Occurrence 33887)

Since for the most part the metrical paratexts are copied next to the title of each book, the attention of the compiler of the Naples manuscript tended to be focused on the same section of the page: in this case and all the others, this scholar only copied the line that was right above the beginning of the text of the Homeric book, disregarding the other option(s). This shows that the compiler was familiar with the traditional structure of a witness of the Iliad and, as a consequence, had certain ‘cultural’ expectations about the place(s) where the information they were looking for (i.e. the metrical titles) would be stored (i.e. next to the unmetrical title and nowhere else). Very likely, their knowledge patterns had already been shaped during the years of their education, when they were taught memorization techniques to best acquire and retain notions: in reading an exemplar of the Iliad, they were aware of the importance of the hypotheseis and the metrical titles, but were only ready to perceive them and commit them to memory in accordance with established models of behavior, that is when they were transcribed in their appropriate, ‘expected’ places.

Notes

[1] Where not otherwise specified, the translation of the paratext’s lines is that of W.R. Paton, with a few adaptions: Greek Anthology, with a translation by W.R. Paton, Vol. III, London- New York 1925 (Loeb Classical Texts), p. 215 (see the following note).

[2] The individual hexameters are also gathered together and transmitted, in the form of a single poem attributed to Stephen of Byzantium, within the corpus of the Greek Anthology (Anth. Gr. IX 385).

[3] A. Severyns, Pomme de discorde et jugement des déesses, «Phoibos», 5 (1950-1951) [= Mélanges J. Hombert], pp. 145-172; F. Pontani, Il mito, la lingua, la morale: tre piccole introduzioni a Omero, «Rivista di Filologia e Istruzione Classica», 133 (2005), pp. 23-74.

Want to read more?

- Brown-Grant, P. Carmassi, G. Drossbach, A. D. Hedeman, V. Turner and I. Ventura (eds.), Inscribing Knowledge in the Medieval Book: The Power of Paratexts, Berlin-Boston 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501513329

- Canart, P. Les anthologies scolaires commentées de la période des Paléologues, à l’école de Maxime Planude et de Manuel Moschopoulos, in: P. Van Deun and C. Macé (eds.), Encyclopedic trends in Byzantium? Proceedings of the international conference held in Leuven, 6-8 May 2009, Leuven 2011, pp. 297-331

- Erll, A. Nünning, A. (eds.), Cultural Memory Studies. An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook, Berlin-Boston-New York 2008. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110207262

- Mazzon, O, Lavorare nell’ombra: Un percorso tra i libri di Giorgio Galesiotes, in: M. Cronier et B. Mondrain (édd.), Le livre manuscrit grec: écritures, matériaux, histoire. Actes du IXe Colloque Internationale de Paléographie Grecque (Paris, 10-15 sept. 2018), Paris 2020, pp. 415-440 (source of image 1, see p. 427)

- Mazzon, O. Leggere, selezionare e raccogliere excerpta nella prima età paleologa. La silloge conservata nel codice greco Neap. II C 32, Alessandria 2021

- Morlet, S. (éd.), Lire en extraits, Lecture et production des textes, de l’Antiquité à la fin du Moyen Âge, Paris 2015

About the author

Ottavia Mazzon obtained her PhD in Classical Philology from the University of Padua and the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris. For the academic year 2021-2022 she is Frances A. Yates Long-term fellow at the Warburg Institute in London. Her research interests intersect the history of the reading and reception of Greek and Latin classics from Byzantium to the Venetian Renaissance, the modes of organization of knowledge, and the dynamics of production and circulation of Greek manuscript books. Her first monograph on the anthologies of excerpts transmitted by MS Neap. II C 32, Leggere, selezionare e raccogliere excerpta nella prima età paleologa, appeared in late 2021 for the Edizioni dell’Orso.

Spread the word!

Share

Cite

This blogpost was written by Febe Schollaert within the framework of an internship at the Database of Byzantine Book Epigrams. She holds a master’s degree in “Greek and Latin Linguistics and Literature” and is currently studying for a master’s degree in “Historical Languages and Linguistics” at Ghent University. Her research interests include narratology; textual criticism and Greek palaeography, with special interest in Byzantine poetry about grammar, in particular orthography. Her first master thesis consists of a study of the orthographical kanones by Niketas of Herakleia (11th-12th c.). She currently focuses on another Byzantine orthographical kanon (transmitted under the names of (Ptocho-)Prodromos, Mazaris or Galaction), and some issues scholars are faced with when editing such a text.

This blogpost was written by Febe Schollaert within the framework of an internship at the Database of Byzantine Book Epigrams. She holds a master’s degree in “Greek and Latin Linguistics and Literature” and is currently studying for a master’s degree in “Historical Languages and Linguistics” at Ghent University. Her research interests include narratology; textual criticism and Greek palaeography, with special interest in Byzantine poetry about grammar, in particular orthography. Her first master thesis consists of a study of the orthographical kanones by Niketas of Herakleia (11th-12th c.). She currently focuses on another Byzantine orthographical kanon (transmitted under the names of (Ptocho-)Prodromos, Mazaris or Galaction), and some issues scholars are faced with when editing such a text.